Dominican Republic increases security force in Dajabon, worsening tensions at border with Haiti

DAJABON, Dominican Republic — Every Monday and Friday morning, the bi-national market town of Dajabon fills up. Thousands of Haitians cross the border into the Dominican Republic and line the streets of Dajabon with everything from clothes to diapers to food. They wait for the Dominican buyers who arrive on buses, motorcycles and in SUVs from cities all over the country, lured by the cheap prices offered by Haitian sellers.

Markets like Dajabon are a lifeline for many Haitians. A 2010 earthquake leveled Haiti’s capital, killing more than 200,000 people. A subsequent cholera epidemic just months later resulted in at least 9,000 more deaths. Government failure followed the disaster, and most Haitians were forced to fend for themselves. Unlike Haiti, the Dominican Republic was left largely untouched by the earthquake even though the two countries share the same island.

The political situation in Haiti has deteriorated over the last few months, resulting in a larger than usual number of migrants trying to cross the border, legally and illegally, according to Dominican security personnel and Haitians at the market. The government of the Dominican Republic has responded with a security crackdown on Haitian migrants, worsening the historically rocky relationship between the two countries.

Haitians in the market say the situation at home has become desperate, with prices rising and the government failing to provide even basic services like electricity. “The government doesn’t work,” Jocquelin Guilloume, 33, who was selling second-hand clothes on the side of the street in Dajabon, told Al Jazeera.

Anti-government protests have erupted in Haiti in recent months, with thousands of protesters marching in the capital, Port-au-Prince, complaining of government corruption. Haiti’s parliament collapsed last week after its mandate expired without an agreement among lawmakers and President Michel Martelly for its extension.

“They’re protesting for the lights,” Guilloume said.

Felix, a 34-year-old Haitian at the Dajabon market who like many who spoke with Al Jazeera declined to give his last name, agreed the main complaint of demonstrators was the lack of electricity, but rising prices are also driving protest. “The cost of living is too high,” Felix said. “Everything is expensive.” More than half of Haiti’s 10 million residents live on less than $2 a day, so even a small increase in the price of goods can have a big impact.

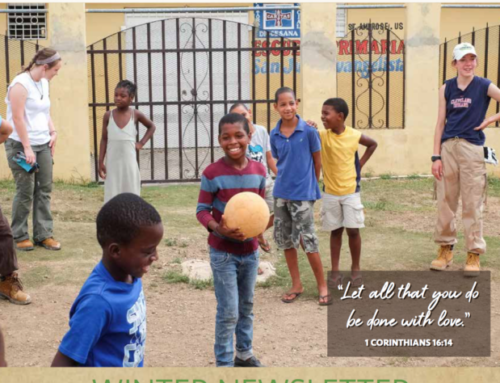

The Dominican government reacted to the protests in Haiti by increasing security forces along the border. In the first two weeks of January, soldiers with CESFRONT, a border security force trained by the United States, stopped about 1,000 Haitians every day trying to cross into the Dominican Republic illegally, local media reported.

A few feet away from the crowded customs crossing in Dajabon, a young CESFRONT soldier, who declined to give his name, watched the border armed with an automatic rifle and knock-off designer sunglasses. “We got an order from high up a few months ago to increase security along the border,” he said.

About 2,000 Haitians are allowed into the Dajabon market twice a week, the soldier said, but they are not allowed to stay. A series of military checkpoints on the road leading out of Dajabon prevents Haitians who are allowed in temporarily for market days from entering further, or permanently, into the Dominican Republic.

Another CESFRONT soldier stationed a few hundred feet away agreed that the security situation has worsened recently. “They have sent in reinforcements along the border because the Haitians are crossing illegally,” the soldier said.

Behind the soldier, Haitians could be seen washing in the shallow river that forms the border between the two countries. It’s known as Massacre River, for colonial era killings as well as the massacre of thousands of Haitians in 1937 ordered by former Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo. Children played and chatted across a fence near the border.

The security crackdown is only the latest of many efforts by the Dominican government to control the flow of Haitian immigrants. Last year, the government decided to rescind citizenship from 210,000 Haitian immigrants, many of whose parents had been given government permits to work in Dominican fields in past decades. The move was widely criticized by human rights groups, but those who lost their citizenship are unable to appeal. “The Dominican Republic is not considerate of Haiti, they don’t care about us,” Wilfride said.

Felix agreed, saying most Haitians want closer ties with the Dominican Republic, but the sentiment is not shared across the border. While many analysts say that hardline anti-Haitian views are held mainly by a small, nationalistic elite, graffiti reading, “Haitians get out” is a common sight in the capital, Santo Domingo.

Rigobto Nunez, a Dominican man living on the street closest to the border with Haiti, predicted that the security situation would only get worse unless Haiti’s economy improves. “Here the people have jobs, but across the border they have nothing,” he said.